膀胱尿路上皮癌的病理诊断进展

作者:龚静 陈铌 周桥(四川大学华西医院病理科)

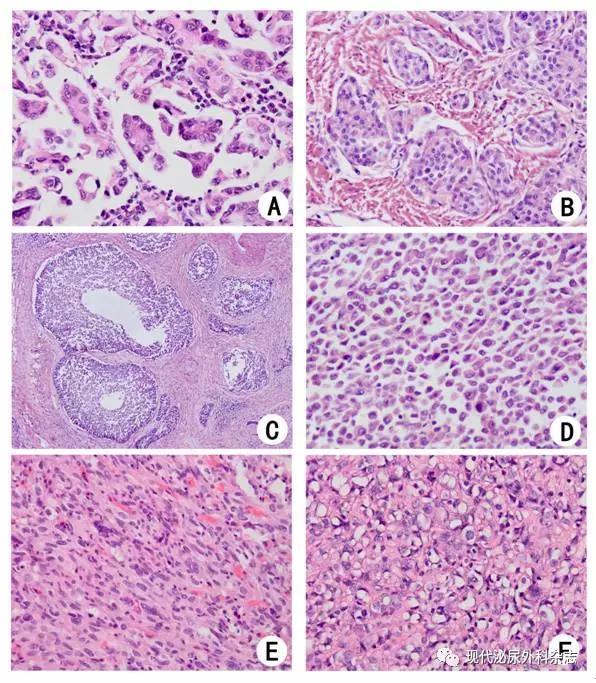

01、浸润性尿路上皮癌变异型

浸润性尿路上皮癌组织学形态多样,除了常见的普通型外,有多种变异型(或亚型)。某些变异型组织学形态类似良性病变,病理医生需要警惕,避免漏诊;某些变异型则需要与其他类型的肿瘤相鉴别;某些变异型侵袭性更高或预后更差,需要在治疗决策与监测中予以考虑[1]。

1.1伴鳞状分化及腺分化的尿路上皮癌(urothelial carcinoma with squamous or glandular differentiation)浸润性尿路上皮癌最常见的变异型是尿路上皮癌伴鳞状分化,其次是伴腺分化。一些研究显示伴有鳞状分化或腺分化的尿路上皮癌预后更差,应采取更积极的治疗[2]。最近两个分别纳入了2444和1013个病例的大宗病例研究显示,与单纯尿路上皮癌相比,具有鳞状或/和腺分化的尿路上皮癌侵袭性更强,发现时病理分期常更晚,但根治术后的预后与相同分期的单纯尿路上皮癌未见明显差异[3-4]。

1.2微乳头型尿路上皮癌(micropapillaryurothelial carcinoma)微乳头型尿路上皮癌(图1A)需与伴有微乳头形态的转移癌相鉴别。该亚型在诊断时常常已有肌层浸润,且20%伴淋巴结转移,根治标本中淋巴结的转移率可达64%[5]。不论微乳头状成分是局灶还是弥漫分布,均提示预后较差[6]。一些学者建议,活检标本在固有层中如有微乳头成分,但未明确有肌层累及时,应再活检;甚至建议不论是否有肌层浸润,都应早期行膀胱切除术,以提高生存率[7-9]。

1.3巢状变异型尿路上皮癌(nested urothelial carcinoma)巢状变异型尿路上皮癌(图1B)组织形态可类似旺炽增生的布氏巢,或腺性膀胱炎,故诊断陷阱较大。该亚型侵袭性强,70%的患者在TURBT标本中即可见固有肌层浸润;大部分患者在诊断时即有淋巴结转移,70%的病例于4~40月内死于肿瘤转移[10]。认识和治疗不足可能是其预后差的原因之一。但亦有报道显示,相同病理分期的巢状变异型与普通型尿路上皮癌行膀胱根治术后,无复发生存率和肿瘤特异性生存率差异不明显[11]。

大巢状变异型(large nested variant)是最近报道的一种新的变异型,肿瘤细胞形态较温和,形成大巢浸润性生长,常浸润肌层,出现间质反应(图1C);但由于癌巢周围边界可较光滑,易被误认为非浸润性尿路上皮肿瘤或病变[12]。2016版WHO泌尿系统肿瘤分类将其列入巢状变异型尿路上皮癌中[13]。

1.4浆细胞样尿路上皮癌(plasmacytoidurothelial carcinoma)浆细胞样型也是预后较差的变异型。其形态学特点是肿瘤细胞核偏位,粘附性差,呈浆细胞样(图1D),可表达CD138,需要与浆细胞瘤/多发性骨髓瘤鉴别[14]。膀胱镜检时,黏膜表面病变可不显著,常仅见黏膜水肿,但该亚型侵袭性强,很易沿腹膜后间隙浸润。确诊时多为pT3-4期,淋巴结转移率达72%,手术切缘阳性率约40%,高于其他尿路上皮癌亚型[15]。该亚型的治疗主要是及时手术,有些学者提出应采用比普通型尿路上皮癌更激进的手术方案[16]。这一亚型对新辅助化疗有一定敏感性,80%患者化疗后肿瘤分期有所下降,但易复发,生存率与单纯手术者无明显差异,长期生存者罕见[17]。

1.5肉瘤样尿路上皮癌(sarcomatoidurothelial carcinoma)肉瘤样尿路上皮癌可显示向上皮及间叶分化的双相特征,间叶成分可为高级别、未分化的梭形细胞肉瘤(图1E),也可为异源性成分,如骨肉瘤、软骨肉瘤、横纹肌肉瘤、平滑肌肉瘤等。研究显示癌及肉瘤样成分具有相同克隆起源[18-19]。该亚型预后差,初诊时常为期晚,伴有转移,平均生存时间约14个月,5年肿瘤特异性生存率约20%,伴有异源性成分时预后更差[20-22]。

1.6淋巴上皮瘤样尿路上皮癌(lymphoepithelioma-like urothelial carcinoma)淋巴上皮瘤样癌形态类似鼻咽部非角化性癌,但无EB病毒感染的证据[23]。该亚型侵袭性强,70%以上的患者在诊断时分期≥pT2。目前最大宗的研究纳入了34个病例,其免疫表型类似于经典的高级别尿路上皮癌,但几乎不表达CK20;预后也与经典的尿路上皮癌相似。纯粹的淋巴上皮瘤样癌或以该成分为主的尿路上皮癌对化疗敏感,预后比局灶性淋巴上皮瘤样癌好[23]。

1.7 富于脂质的尿路上皮癌(lipid-rich urothelial carcinoma)该变异型癌细胞胞质中含有空泡(图1G),电镜检查及新鲜组织脂肪染色证实胞质内空泡为脂质[24-25],常与普通的高级别尿路上皮癌并存,免疫表型亦相似。病理诊断上需与脂肪肉瘤、印戒细胞癌等鉴别[24]。该变异型诊断时常为进展期,预后差,45%患者诊断时即有淋巴结转移,60%患者在16~58个月内死亡[24]。

1.8其他罕见亚型 除以上变异型,文献中还报道了一些更罕见的变异型,如透明细胞型、伴有巨细胞的变异型、伴有大量黏液样间质的变异型[26-27]等,尚需积累更多的资料以了解其生物学行为。

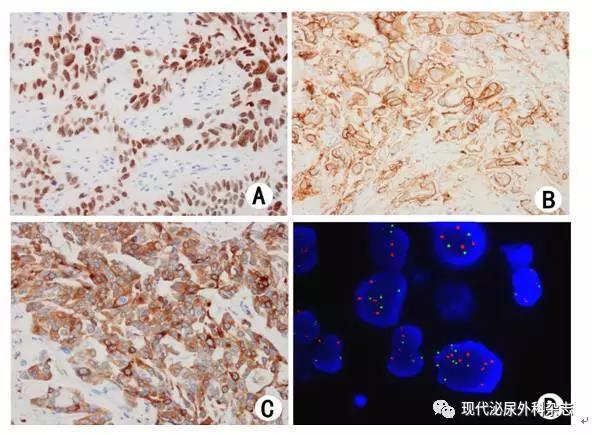

02、尿路上皮癌的免疫组化和分子诊断

2.1免疫组化标记在诊断中的应用

大部分尿路上皮病变可通过HE染色切片诊断,部分疑难病例则需借助免疫组化标记来帮助判断。在转移癌的鉴别上,也常需借助免疫组化。尿路上皮可表达高分子量CK(HMWCK)、CK5/6和p63等常见于鳞状上皮的标记,同时也表达部分腺上皮标记,如CK7和CK20等。但这些标记并非特异的尿路上皮标记,需借助其组合辅助诊断和鉴别诊断。尿路上皮癌分化差时,这些标记的敏感性也降低,故辅助作用有限。因此,寻找更敏感、更特异的尿路上皮癌标记是近年来分子病理研究的一个重要内容。以下介绍几种近年来发现的可辅助尿路上皮癌诊断的免疫标记。

2.1.1 GATA3 GATA3是GATA转录因子家族成员。基因表达谱筛选发现GATA3是尿路上皮的分化标记[28],表达于67%~91.6%的尿路上皮癌[29-33](图2A);在非浸润尿路上皮癌中的阳性率稍高于浸润性尿路上皮癌[33]。在浸润性尿路上皮癌及各种变异型中,普通型尿路上皮癌GATA3阳性率最高,其次为微乳头型和浆细胞样型[34-35]。肉瘤样变异型GATA3阳性率报道差异较大[20, 34],多形性未分化肉瘤样区域或明显的异源性成份通常为阴性[20]。

在来源未明的转移癌的鉴别诊断中,GATA3阳性提示可能为尿路上皮癌;但应注意其他一些肿瘤也可表达GATA3。阳性率较高的是乳腺癌,浸润性导管癌阳性率为67-91%,小叶癌则几乎100%阳性[29, 36]。其他肿瘤如皮肤基底细胞癌、鳞状细胞癌、胰腺导管腺癌、子宫内膜腺癌、滋养叶细胞肿瘤、卵黄囊瘤、间皮瘤、涎腺肿瘤[29],以及副节瘤(包括发生在膀胱的)等,也可表达GATA3[37]。

2.1.2 UroplakinⅢ和UroplakinⅡ Uroplakin家族分子包括四个主要成员:Ⅰa、Ⅰb、Ⅱ和Ⅲ,是尿路上皮分化终末阶段的标记,主要在尿路上皮的伞盖细胞中表达[38]。UroplakinⅢ是最早用于尿路上皮癌诊断的分子(图2B),也是特异性最高的一个标记,文献中尚未见其他肿瘤表达的报道;但其敏感性随肿瘤级别增高明显降低[39],实际应用价值有限。

UroplakinⅡ也是判断尿路上皮分化的标记[40](图2C),其敏感性高于UroplakinⅢ,浆细胞样型和巢状型尿路上皮癌中阳性率几乎100%,转移性尿路上皮癌中阳性率也较高[40]。UroplakinⅡ也具有较好的特异性,其他部位如呼吸道、消化道、乳腺等部位的多种肿瘤都未见UroplakinⅡ的表达[33, 40-42],但尚需积累更多数据。

2.1.3 S100P S100P(胎盘S100)在普通尿路上皮癌和各种尿路上皮癌变异型中阳性率均较高[28, 32, 43],总体阳性率甚至高于GATA3[35]。但S100P除了在尿路上皮中表达外,在胎盘、胰腺导管腺癌、胆管癌、乳腺癌、结肠癌、非小细胞肺癌和前列腺癌等组织中也有表达[44]。

2.2 荧光原位杂交在尿液细胞学中的诊断价值 通过尿脱落细胞学检查筛查膀胱癌,具有无创、易行、快速等优点,但敏感性不高。近年来,尿液细胞样本的荧光原位杂交(FISH)检查得到较广泛应用(图2D)。UroVysion是美国FDA批准使用的一组荧光原位杂交探针组合,用于患者尿液标本监测肿瘤复发,或对以前没有尿路上皮癌病史、出现肉眼或镜下血尿的患者进行尿路上皮癌筛查。UroVysion探针组合包含4种荧光标记DNA探针的混合物,分别是位于9号染色体的9p21位点特异性探针和3号、7号、17号染色体着丝粒探针。检测的敏感性和特异性均高于尿脱落细胞学[45]。文献报道3号、7号、17号染色体着丝粒探针对尿路上皮癌的敏感性分别为73.7%,76.2%和61.9%;9p21纯合子缺失对尿路上皮癌的敏感性为28.6%[46]。UroVysion的检测方法是基于这些探针的组合,与常规尿脱落细胞学相结合,其敏感性和特异性分别可达到69-87%和89-96%[45]。国内亦有商品化试剂,研究显示其敏感性可达94.3%,特异性可达81.3%[47]。但应注意膀胱的炎性病变可干扰检测结果的评价。

2.3 微小RNA(miRNAs)检测在膀胱癌诊断中的应用 微小RNA(microRNAs,miRNAs)这一类非编码RNA分子在肿瘤进展中的重要作用近年来得到广泛和深入的研究。一些miRNAs的异常不仅在肿瘤组织中存在,也能在血液、尿液中检测到,尤其尿液中miRNAs的检测具有无创、便捷的特点,有很好的临床诊断应用前景。利用尿液miRNAs检测诊断泌尿系统肿瘤如膀胱癌、肾癌、前列腺癌是近年来研究的热点。在膀胱癌患者尿液中发现有异常表达的多种miRNAs,如下调的miR-125b、miR145、miR192、miR200a等和上调的miR-96、miR126、135b、miR-182、miR-183等[48-49]。对多组尿液miRNAs诊断研究数据的Meta分析显示,miRNAs对膀胱癌诊断的总体敏感性和特异性分别为74.8%和74.2%,miRNAs分子组合优于单一miRNA,尿液离心后上清液miRNAs的检测优于尿沉渣[48-49]。尿液miRNAs分子检测可望成为膀胱尿路上皮癌无创性诊断的新方法。

2.4 TERT基因启动子突变的诊断应用 端粒酶调节染色体端粒的长度,是决定细胞进入复制、衰老还是永生化状态的重要因素。正常体细胞中其活性几乎不能检测到,而恶性黑色素瘤、膀胱癌、胶质瘤等多种肿瘤中有端粒酶的表达/活性。端粒逆转录酶(TERT,telomerase reverse transcriptase)基因启动子区域的激活突变可能是其主要机制[50]。

TERT基因启动子突变是尿路上皮癌中常见的突变,最常见的突变位点是C228T,其次是C250T [51]。膀胱尿路上皮癌中TERT基因启动子突变率为47-85%[52],特异性为73-90%[51],且可通过尿液样本检测。非浸润性与浸润性尿路上皮癌中TERT基因启动子的突变率相似,新诊断病例与复发病例中检出率无明显差别。在容易误诊为良性病变的巢状变异型、大巢状变异型尿路上皮癌和内翻性生长的尿路上皮癌中也有较高的突变检出率[53],可辅助尿路上皮癌的鉴别诊断,但需注意少部分内翻性乳头状瘤亦能检出TERT基因启动子突变[54]。TERT基因启动子突变与膀胱癌的分级、分期及患者预后是否相关尚有争议[52]。有研究显示TERT mRNA高表达的患者预后更差[55]。

2.5 FGFR3突变在尿路上皮癌中的诊断意义 成纤维细胞生长因子受体3(FGFR3,fibroblast growth factor 3)基因突变是乳头状尿路上皮癌发生的主要机制之一,常见于低级别乳头状、非肌层浸润性尿路上皮癌[56]。60%非肌层浸润性尿路上皮癌具有FGFR3的活化性点突变,低级别和高级别尿路上皮癌中突变率分别为73%和32%[57]。近年来尿液脱落细胞FGFR3突变检测应用于膀胱癌的早期诊断和术后复发监测得到了较多关注[58-59];联合TERT基因启动子突变检测可增加敏感性[51]。具有FGFR3突变的非肌层浸润性癌复发率更高,复发时间也更短[58]。FGFR3突变与增殖指数Ki-67(MIB-1)、细胞周期调控分子P53,联合EORTC(欧洲癌症研究与治疗组织)风险评分用于膀胱尿路上皮癌患者复发、进展情况的预测,也优于单纯的EORTC风险评估[59]。

03、小结

尿路上皮癌组织学形态多变,病理医生需要仔细识别各种变异型。临床医生了解各种变异型的生物学行为特点,有助于制定更准确和个性化的治疗、监测方案。尿路上皮癌免疫组化标记的进展为尿路上皮癌组织病理学诊断提供了较大帮助;基于染色体、基因异常的分子检测,为尿路上皮癌的分子病理诊断和临床监测提供了许多新的信息和更多方案的选择,将较广泛地应用于临床实践。

▲图1 浸润性尿路上皮癌变异型(HE染色)

A:微乳头状型;B:巢状型;C:大巢状变异型;D:浆细胞样型;E:肉瘤样型;F:富于脂质型

▲图2 尿路上皮癌的免疫组织化学染色与荧光原位杂交检测(A-C:免疫组织化学染色,D:荧光原位杂交)

A:GATA3细胞核阳性;B:UroplakinⅢ细胞膜阳性;C:UroplakinⅡ细胞浆阳性;D:3号和7号染色体为多体(绿色:3号染色体,红色:7号染色体)

参考文献:

[1] XYLINAS E,RINK M,ROBINSON BD,et al. Impact of histological variants on oncological outcomes of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder treated with radical cystectomy [J]. Eur J Cancer,2013,49(8):1889-1897.

[2] ERDEMIR F,TUNC M,OZCAN F,et al. The effect of squamous and/or glandular differentiation on recurrence, progression and survival in urothelial carcinoma of bladder [J]. Int Urol Nephrol,2007,39(3):803-807.

[3] KIM SP,FRANK I,CHEVILLE JC,et al. The impact of squamous and glandular differentiation on survival after radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma [J]. J Urol,2012,188(2):405-409.

[4] MITRA AP,BARTSCH CC,BARTSCH G, JR.,et al. Does presence of squamous and glandular differentiation in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder at cystectomy portend poor prognosis? An intensive case-control analysis [J]. Urol Oncol,2014,32(2):117-127.

[5] MONN MF,KAIMAKLIOTIS HZ,PEDROSA JA,et al. Contemporary bladder cancer: variant histology may be a significant driver of disease [J]. Urol Oncol,2015,33(1):18 e15-20.

[6] COMPERAT E,ROUPRET M,YAXLEY J,et al. Micropapillary urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathological analysis of 72 cases [J]. Pathology,2010,42(7):650-654.

[7] HANSEL DE,AMIN MB,COMPERAT E,et al. A contemporary update on pathology standards for bladder cancer: transurethral resection and radical cystectomy specimens [J]. Eur Urol,2013,63(2):321-332.

[8] KAMAT AM,DINNEY CP,GEE JR,et al. Micropapillary bladder cancer: a review of the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience with 100 consecutive patients [J]. Cancer,2007,110(1):62-67.

[9] LOPEZ-BELTRAN A,MONTIRONI R,BLANCA A,et al. Invasive micropapillary urothelial carcinoma of the bladder [J]. Hum Pathol,2010,41(8):1159-1164.

[10] WASCO MJ,DAIGNAULT S,BRADLEY D,et al. Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 30 pure and mixed cases [J]. Hum Pathol,2010,41(2):163-171.

[11] LINDER BJ,FRANK I,CHEVILLE JC,et al. Outcomes following radical cystectomy for nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: a matched cohort analysis [J]. J Urol,2013,189(5):1670-1675.

[12] COX R,EPSTEIN JI. Large nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: 23 cases mimicking von Brunn nests and inverted growth pattern of noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2011,35(9):1337-1342.

[13] MOCH H,HUMPHREY PA,ULBRIGHT TM,et al. WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs [M]. 4th edn. Lyon: IARC, 2016:81-98.

[14] FRITSCHE HM,BURGER M,DENZINGER S,et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: histological and clinical features of 5 cases [J]. J Urol,2008,180(5):1923-1927.

[15] KECK B,STOEHR R,WACH S,et al. The plasmacytoid carcinoma of the bladder--rare variant of aggressive urothelial carcinoma [J]. Int J Cancer,2011,129(2):346-354.

[16] KAIMAKLIOTIS HZ,MONN MF,CARY KC,et al. Plasmacytoid variant urothelial bladder cancer: is it time to update the treatment paradigm? [J]. Urol Oncol,2014,32(6):833-838.

[17] DAYYANI F,CZERNIAK BA,SIRCAR K,et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma, a chemosensitive cancer with poor prognosis, and peritoneal carcinomatosis [J]. J Urol,2013,189(5):1656-1661.

[18] SUNG MT,WANG M,MACLENNAN GT,et al. Histogenesis of sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: evidence for a common clonal origin with divergent differentiation [J]. J Pathol,2007,211(4):420-430.

[19] ARMSTRONG AB,WANG M,EBLE JN,et al. TP53 mutational analysis supports monoclonal origin of biphasic sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the urinary bladder [J]. Mod Pathol,2009,22(1):113-118.

[20] FATIMA N,CANTER DJ,CARTHON BC,et al. Sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a contemporary clinicopathologic analysis of 37 cases [J]. Can J Urol,2015,22(3):7783-7787.

[21] WRIGHT JL,BLACK PC,BROWN GA,et al. Differences in survival among patients with sarcomatoid carcinoma, carcinosarcoma and urothelial carcinoma of the bladder [J]. J Urol,2007,178(6):2302-2306; discussion 2307.

[22] WANG J,WANG FW,LAGRANGE CA,et al. Clinical features of sarcomatoid carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the urinary bladder: analysis of 221 cases [J]. Sarcoma,2010,2010.

[23] WILLIAMSON SR,ZHANG S,LOPEZ-BELTRAN A,et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2011,35(4):474-483.

[24] LOPEZ-BELTRAN A,AMIN MB,OLIVEIRA PS,et al. Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, lipid cell variant: clinicopathologic findings and LOH analysis [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2010,34(3):371-376.

[25] LEROY X,GONZALEZ S,ZINI L,et al. Lipoid-cell variant of urothelial carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of five cases [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2007,31(5):770-773.

[26] TAVORA F,EPSTEIN JI. Urothelial carcinoma with abundant myxoid stroma [J]. Hum Pathol,2009,40(10):1391-1398.

[27] SAMARATUNGA H,DELAHUNT B. Recently described and unusual variants of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder [J]. Pathology,2012,44(5):407-418.

[28] HIGGINS JP,KAYGUSUZ G,WANG L,et al. Placental S100 (S100P) and GATA3: markers for transitional epithelium and urothelial carcinoma discovered by complementary DNA microarray [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2007,31(5):673-680.

[29] MIETTINEN M,MCCUE PA,SARLOMO-RIKALA M,et al. GATA3: a multispecific but potentially useful marker in surgical pathology: a systematic analysis of 2500 epithelial and nonepithelial tumors [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2014,38(1):13-22.

[30] ZHAO L,ANTIC T,WITTEN D,et al. Is GATA3 expression maintained in regional metastases?: a study of paired primary and metastatic urothelial carcinomas [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2013,37(12):1876-1881.

[31] CHANG A,AMIN A,GABRIELSON E,et al. Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2012,36(10):1472-1476.

[32] GULMANN C,PANER GP,PARAKH RS,et al. Immunohistochemical profile to distinguish urothelial from squamous differentiation in carcinomas of urothelial tract [J]. Hum Pathol,2013,44(2):164-172.

[33] TIAN W,GUNER G,MIYAMOTO H,et al. Utility of uroplakin II expression as a marker of urothelial carcinoma [J]. Hum Pathol,2015,46(1):58-64.

[34] LIANG Y,HEITZMAN J,KAMAT AM,et al. Differential expression of GATA-3 in urothelial carcinoma variants [J]. Hum Pathol,2014,45(7):1466-1472.

[35] PANER GP,ANNAIAH C,GULMANN C,et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of novel and traditional markers associated with urothelial differentiation in a spectrum of variants of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder [J]. Hum Pathol,2014,45(7):1473-1482.

[36] GONZALEZ RS,WANG J,KRAUS T,et al. GATA-3 expression in male and female breast cancers: comparison of clinicopathologic parameters and prognostic relevance [J]. Hum Pathol,2013,44(6):1065-1070.

[37] SO JS,EPSTEIN JI. GATA3 expression in paragangliomas: a pitfall potentially leading to misdiagnosis of urothelial carcinoma [J]. Mod Pathol,2013,26(10):1365-1370.

[38] WU XR,LIN JH,WALZ T,et al. Mammalian uroplakins. A group of highly conserved urothelial differentiation-related membrane proteins [J]. J Biol Chem,1994,269(18):13716-13724.

[39] PARKER DC,FOLPE AL,BELL J,et al. Potential utility of uroplakin III, thrombomodulin, high molecular weight cytokeratin, and cytokeratin 20 in noninvasive, invasive, and metastatic urothelial (transitional cell) carcinomas [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2003,27(1):1-10.

[40] SMITH SC,MOHANTY SK,KUNJU LP,et al. Uroplakin II outperforms uroplakin III in diagnostically challenging settings [J]. Histopathology,2014,65(1):132-138.

[41] HOANG LL,TACHA DE,QI W,et al. A newly developed uroplakin II antibody with increased sensitivity in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder [J]. Arch Pathol Lab Med,2014,138(7):943-949.

[42] HOANG LL,TACHA D,BREMER RE,et al. Uroplakin II (UPII), GATA3, and p40 are Highly Sensitive Markers for the Differential Diagnosis of Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma [J]. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol,2015,23(10):711-716.

[43] CHUANG AY,DEMARZO AM,VELTRI RW,et al. Immunohistochemical differentiation of high-grade prostate carcinoma from urothelial carcinoma [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2007,31(8):1246-1255.

[44] JIANG H,HU H,TONG X,et al. Calcium-binding protein S100P and cancer: mechanisms and clinical relevance [J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol,2012,138(1):1-9.

[45] SAROSDY MF,KAHN PR,ZIFFER MD,et al. Use of a multitarget fluorescence in situ hybridization assay to diagnose bladder cancer in patients with hematuria [J]. J Urol,2006,176(1):44-47.

[46] SOKOLOVA IA,HALLING KC,JENKINS RB,et al. The development of a multitarget, multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization assay for the detection of urothelial carcinoma in urine [J]. J Mol Diagn,2000,2(3):116-123.

[47] 陈铌,龚静,曾浩,等. 尿脱落细胞荧光原位杂交检测诊断膀胱肿瘤的价值 [J]. 四川大学学报:医学版,2011,42(1):109-113.

[48] OUYANG H,ZHOU Y,ZHANG L,et al. Diagnostic Value of MicroRNAs for Urologic Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [J]. Medicine (Baltimore),2015,94(37):e1272.

[49] CHENG Y,DENG X,YANG X,et al. Urine microRNAs as biomarkers for bladder cancer: a diagnostic meta-analysis [J]. Onco Targets Ther,2015,8:2089-2096.

[50] LIU X,WU G,SHAN Y,et al. Highly prevalent TERT promoter mutations in bladder cancer and glioblastoma [J]. Cell Cycle,2013,12(10):1637-1638.

[51] ALLORY Y,BEUKERS W,SAGRERA A,et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutations in bladder cancer: high frequency across stages, detection in urine, and lack of association with outcome [J]. Eur Urol,2014,65(2):360-366.

[52] VINAGRE J,PINTO V,CELESTINO R,et al. Telomerase promoter mutations in cancer: an emerging molecular biomarker? [J]. Virchows Arch,2014,465(2):119-133.

[53] ZHONG M,TIAN W,ZHUGE J,et al. Distinguishing nested variants of urothelial carcinoma from benign mimickers by TERT promoter mutation [J]. Am J Surg Pathol,2015,39(1):127-131.

[54] CHENG L,DAVIDSON DD,WANG M,et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutation analysis of benign, malignant and reactive urothelial lesions reveals a subpopulation of inverted papilloma with immortalizing genetic change [J]. Histopathology,2016:doi: 10.1111/his.12920.

[55] BORAH S,XI L,ZAUG AJ,et al. Cancer. TERT promoter mutations and telomerase reactivation in urothelial cancer [J]. Science,2015,347(6225):1006-1010.

[56] BAKKAR AA,WALLERAND H,RADVANYI F,et al. FGFR3 and TP53 gene mutations define two distinct pathways in urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder [J]. Cancer Res,2003,63(23):8108-8112.

[57] BURGER M,VAN DER AA MN,VAN OERS JM,et al. Prediction of progression of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer by WHO 1973 and 2004 grading and by FGFR3 mutation status: a prospective study [J]. Eur Urol,2008,54(4):835-843.

[58] COUFFIGNAL C,DESGRANDCHAMPS F,MONGIAT-ARTUS P,et al. The Diagnostic and Prognostic Performance of Urinary FGFR3 Mutation Analysis in Bladder Cancer Surveillance: A Prospective Multicenter Study [J]. Urology,2015,86(6):1185-1191.

[59] VAN RHIJN BW,ZUIVERLOON TC,VIS AN,et al. Molecular grade (FGFR3/MIB-1) and EORTC risk scores are predictive in primary non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer [J]. Eur Urol,2010,58(3):433-441.

本站欢迎原创文章投稿,来稿一经采用稿酬从优,投稿邮箱tougao@ipathology.com.cn

相关阅读

数据加载中

数据加载中

我要评论

热点导读

-

淋巴瘤诊断中CD30检测那些事(五)

强子 华夏病理2022-06-02 -

【以例学病】肺结节状淋巴组织增生

华夏病理 华夏病理2022-05-31 -

这不是演习-一例穿刺活检的艰难诊断路

强子 华夏病理2022-05-26 -

黏液性血性胸水一例技术处理及诊断经验分享

华夏病理 华夏病理2022-05-25 -

中老年女性,怎么突发喘气困难?低度恶性纤维/肌纤维母细胞性肉瘤一例

华夏病理 华夏病理2022-05-07

共0条评论